By DeNeen L. Brown

April 15, 2021 at 7:30 a.m. EDT

At 8 p.m. on Jan. 12, 1865, days after his “march to the sea,” Maj. Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman met with 20 Black ministers on the second floor of his headquarters in Savannah, Ga.

The Civil War would soon end, and the matter at hand that night was urgent.

Sherman had called the Black ministers to confer with him and President Lincoln’s Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton. On the agenda were pressing questions: How would the country provide for the protection of thousands of Black refugees who had followed Sherman’s army since it invaded Georgia? How would thousands of newly freed Black people survive economically after more than 200 years of bondage and unpaid labor?

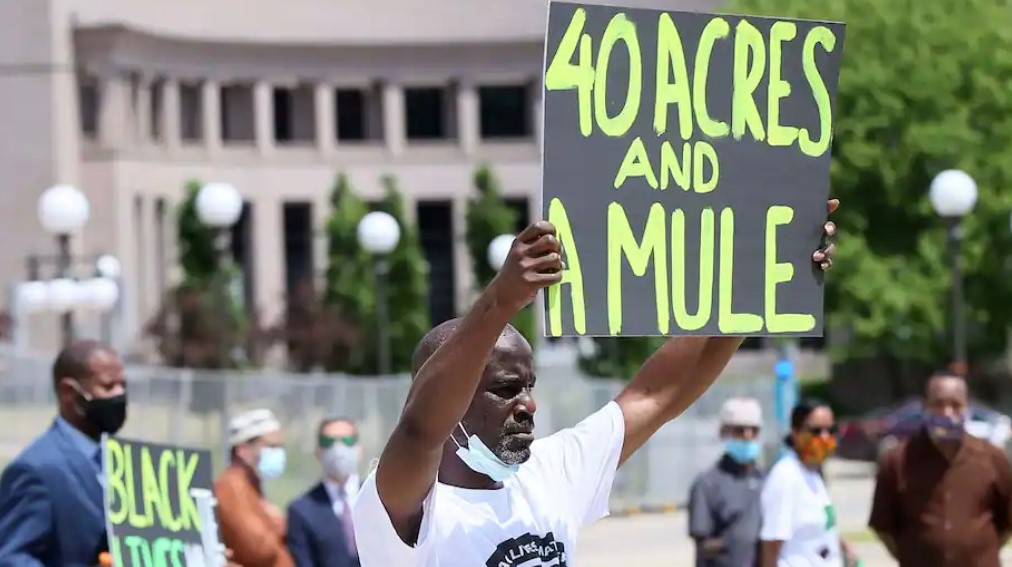

Four days after the meeting, Sherman would issue Special Field Order, No. 15, confiscating Confederate land along the rice coast. Sherman would later order “40 acres and a mule” to thousands of Black families, which historians would later refer to as the first act of reparations to enslaved Black people.

But the order would be short-lived. After Lincoln’s assassination on April 14, 1865, the order would be reversed and the land given to Black families would be rescinded and returned to White Confederate landowners. More than 100 years later, “40 acres and a mule” would remain a battle cry for Black people demanding reparations for slavery.

On Wednesday — the anniversary of Lincoln’s death — the House Judiciary Committee approved a bill that would create a commission on slavery reparations. H.R. 40 takes its name from the phrase “40 acres and a mule.” It was first introduced in Congress in 1989 by Rep. John Conyers Jr. (D-Mich.) after the passage of the Civil Liberties Act of 1988, which paid reparations to Japanese-Americans forced into internment camps by President Franklin D. Roosevelt during World War II.

Rep. Shelia Jackson Lee (D-Tex.) hailed the vote as the first step on a “path to restorative justice” for slavery and the brutal racial oppression that followed it.

The history of 40 acres and a mule began on that evening in January 1865 when the 20 Black ministers met with Sherman and Stanton.

Among the ministers were: John Cox, 58, enslaved in Savannah until he bought his freedom for $1,100; William Gaines, 41, born in Georgia an enslaved person “owned” by former U.S. Sen. Robert Toombs “until the Union forces freed me.”

The ministers had chosen as their spokesman the Rev. Garrison Frazier, 67, who had purchased his own freedom along with his wife’s eight years earlier for $1,000 in gold and silver.

Sherman and Stanton asked Frazier what he understood about slavery and Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation.

Sherman and Stanton asked Frazier how he thought the newly freed Black people could best take care of themselves.

His answer would remain one of the most eloquent arguments for reparations in 156 years: “The way we can best take care of ourselves is to have land, and turn it, and till it by our own labor — that is, by the labor of the woman and children and old men; and we can soon maintain ourselves and have something to spare.”

Frazier added: “We want to be placed on land until we are able to buy it and make it our own.”

Stanton later acknowledged that this was “the first time in the history of this nation when the representatives of this government had gone to these poor, debased people to ask them what they wanted for themselves.”

Four days after that meeting, Sherman seized the coastline from Charleston, S.C., to St. John’s River, Fla., according to the Library of Congress.

“The islands from Charleston south, the abandoned rice fields along the rivers for 30 miles back from the sea, and the country bordering the St. John’s River, Florida, are reserved and set apart for the settlement of the negroes now made free by the acts of war and the proclamation of the President of the United States,” Sherman ordered.

Sherman reminded those reading the orders that “the negro is free, and must be dealt with as such. He cannot be subjected to conscription, or forced military service, save by the written orders of the highest military authority of the department, under such regulations as the President or Congress may prescribe.”

The order carved out 400,000 acres of land confiscated or abandoned by Confederates. Sherman ordered Brig. Gen. Rufus Saxton to divvy up the land. Each family of formerly enslaved Black people would get up to 40 acres. The Army would lend them mules no longer in use.

In the next few months, thousands of Black people traveled to the shores and began working the land.

But those dreams were short-lived.

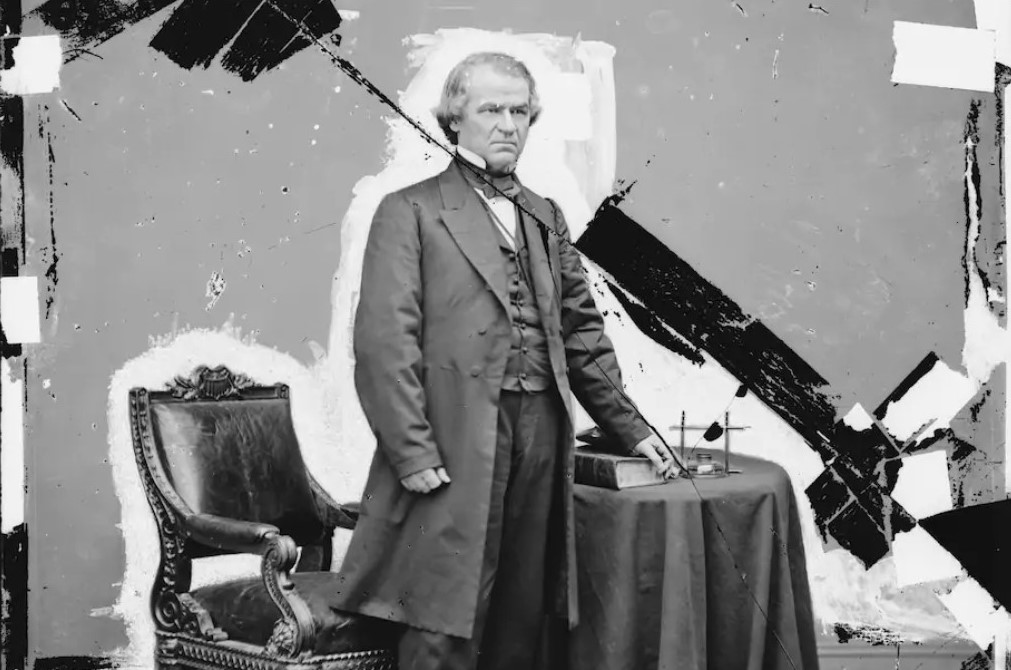

On May 29, 1865, President Andrew Johnson issued an amnesty proclamation, according to the National Archives.

“By the latter part of 1865, thousands of freed people were abruptly evicted from land that had been distributed to them through Special Field Orders No. 15,” according to the National Archives account. “With the exception of a small number who had legal land titles, freed people were removed from the land as a result of President Johnson’s restoration program.”

Thousands of Black people left without land were eventually forced into sharecropping and peonage.

It is time, Jackson Lee said, to face that history and compensate the descendants of slavery for it. But Republicans and some Democrats oppose reparations, so whether the promise of 40 acres and a mule will ever become a reality remains uncertain.

SOURCE: https://www.washingtonpost.com/history/2021/04/15/40-acres-mule-slavery-reparations/

Leave A Comment