If we are true to our Declaration that “We hold these Truths to be self-evident, that all Men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty, and the Pursuit of Happiness….” then we must restore to our people whose “Inalienable Rights” to Life, Liberty and Pursuit of Happiness” we took or allowed to be taken from them without their consent or just cause. To restore these “Inalienable Rights” which we took or allowed to be taken from our people without their consent or just cause, we must pay the reparations debt we owe to them by giving their descendants their inheritances that would have inured to their Life, Liberty and Pursuit of Happiness.

PETITION TO CONGRESS:

FEATURED HISTORICALS:

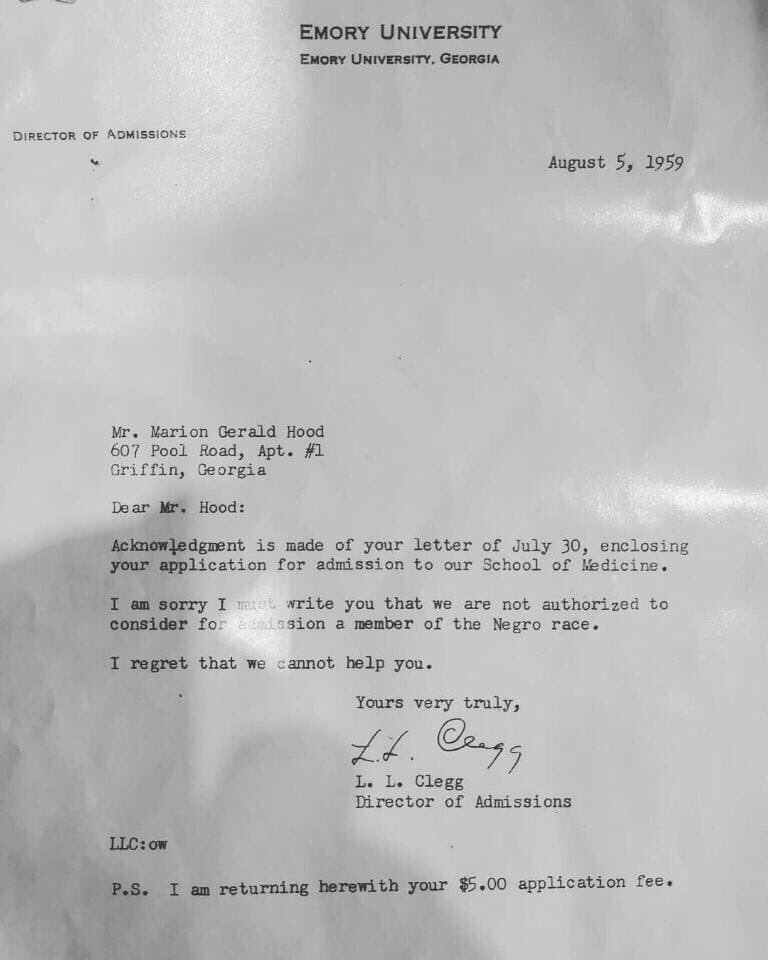

In 1959, Marion Gerald Hood was denied admittance to Emory University School of Medicine due to his race. He is African American.

Jim Crow Laws, enacted by white Democrats in the South during the Reconstructionist period in the late 19th century, mandated legal separation of races. These laws remained in effect until the mid-1960s. They were the basis for Dr. Hood’s (yes, doctor!!) rejection from Emory.

Dr. Hood went on to attend Loyola University Chicago Stritch School of Medicine. He was a practicing OBGYN and now is semi-retired working part-time at a clinic that treats patients regardless of their ability to pay.

His rejection letter is making the rounds on the Internet on this, the 59th anniversary, and it caused me to think. Lots of stuff causes me to think, but this got me thinking deeper.

“It’s a shame it took 60 years, but it’s moving in the right direction there are still barriers,” says Dr. Hood. “I don’t hold them personally responsible for what happened to me. They were just following the rule of the good ol’ South in those days.”

If you want to see Dr. Hood’s talk about why he got into medicine, click here: Georgia Man Reflects on Medical School Racial Denial on 59th Anniversary

I’m so, so grateful that race doesn’t matter to me, or most people, these days—despite what the news media and the loud voices on social media want us to believe. Are there racial and socio-economic barriers? Yes. Are things dire and bleak? I see progress.

I’m happy to receive the expertise of my healthcare providers regardless of what they look like. I’m much more interested in the makeup of their brains than the makeup of their skin tone. Only one of those body parts will save my life.

I got a jones to look up some facts and numbers about minorities and medical schools.

The first African American doctor graduated from a US medical school in 1847, also the year the American Medical Association formed. Two years later, in 1849, the first female graduated from a US medical school. Sadly, it wasn’t until 15 years later, in 1864, the first African American woman graduated. Her name was Rebecca Lee Crumpler.

Interestingly, today, African Americans still make up a smaller percentage of admissions into medical schools. White admissions have dropped in the last 35 years, but the only significant minority gain has been by Asians. Latinos have fared only a little better, but African Americans and Native Americans/Alaska Natives have not seen a significant increase in admissions.

African survivals in black American culture. The once widely held view that traces of the African heritage had been virtually extinguished in the Southern colonies and states has now been generally discarded. John Blassingame devotes the first third of his study The Slave Community to two long chapters. Blassingame and other historians have also pointed to the African influence on various artifacts, and the skills associated with them, in the South–for example, basket weaving, wood carving, pottery, the making of musical instruments, some architectural features, and many agricultural practices. “Cultural creolization” through which American ways were necessarily absorbed, but adapted, articulated, and understood with the aid of “African cultural grammars.” Joyner was writing of an area of great plantations, with perhaps the highest density of slave population on the North American mainland, where African influence was at its strongest. These special circumstances bred a distinct creole language, Gullah, the result of the convergence of a number of African languages with English. Clearly, many of the conditions of cultural creolization on the South Carolina sea islands were not replicated elsewhere.

Share This Story, Choose Your Platform!

Share This Story, Choose Your Platform!

Share This Story, Choose Your Platform!

Share This Story, Choose Your Platform!

John Mercer Langston was the first black man to become a lawyer when he passed the bar in Ohio in 1854. When he was elected to the post of Town Clerk for Brownhelm, Ohio, in 1855 Langston became one of the first African Americans ever elected to public office in America. John Mercer Langston was also the great-uncle of Langston Hughes, famed poet of the Harlem Renaissance.

Share This Story, Choose Your Platform!

Share This Story, Choose Your Platform!

Blassingame has described the “hands-off” policy pursued by one Florida slave owner, and according to Theodore Rosengarten, one South Carolina planter, Thomas B Chaplin, took little interest in his slaves as individuals or in their family Arrangements. In his journal, he registered the births of slave children and also of his words. The only difference was that he named the horses’ sires but not the slaves’ fathers. More than half of the slaves in 1860 lived on plantations containing 20 or more slaves, it is obvious that only a small minority of Planter’s could personally supervise every detail of the work – let alone, one might add, the rest of the Slaves Life. As long as their work was not unsatisfactory and they refrained from serious misdemeanors, many slaves have little personal contact with whites and only occasionally have to act out the rituals of deference. Once again, must be emphasized that the situation on smaller farms and the relationship between small owners and their slaves were rather different.

In fact, U.S. Government also accepted responsibility to pay reparations to former slaveholders. In 1862 the federal government set up a commission to compensate slaveholders who did not join the Confederacy. See, Act of Congress that set up the commission.

In fact, U.S. Government also accepted responsibility to pay reparations to former slaveholders. In 1862 the federal government set up a commission to compensate slaveholders who did not join the Confederacy. See, Act of Congress that set up the commission.