John Mercer Langston was the first black man to become a lawyer when he passed the bar in Ohio in 1854. When he was elected to the post of Town Clerk for Brownhelm, Ohio, in 1855 Langston became one of the first African Americans ever elected to public office in America. John Mercer Langston was also the great-uncle of Langston Hughes, famed poet of the Harlem Renaissance.

Share This Story, Choose Your Platform!

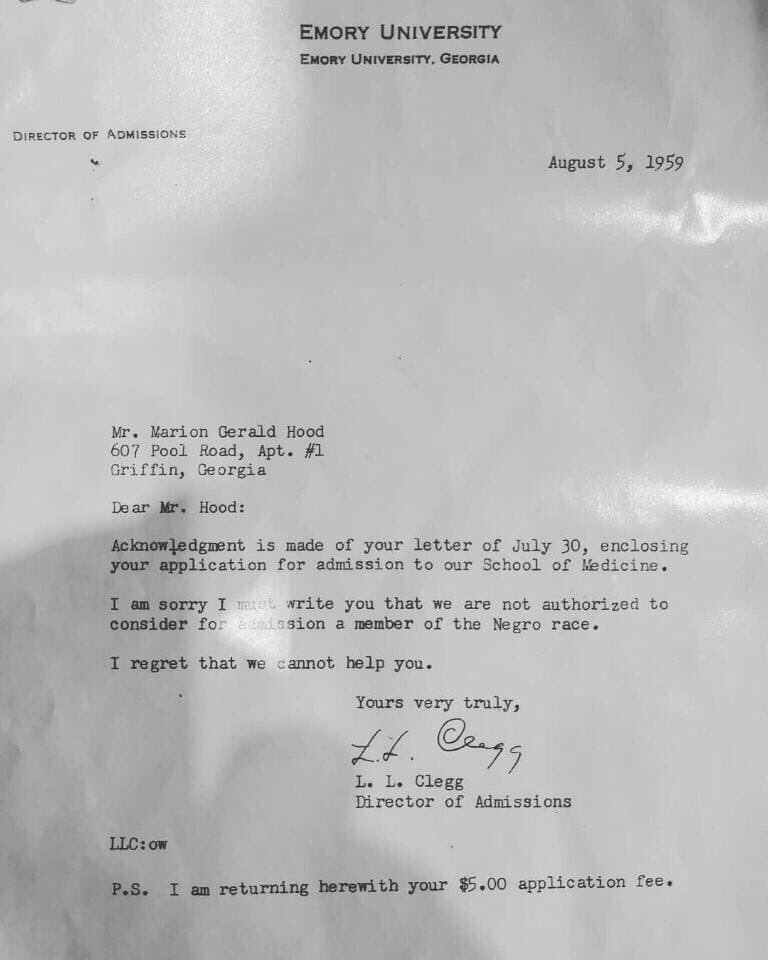

In 1959, Marion Gerald Hood was denied admittance to Emory University School of Medicine due to his race. He is African American.

Jim Crow Laws, enacted by white Democrats in the South during the Reconstructionist period in the late 19th century, mandated legal separation of races. These laws remained in effect until the mid-1960s. They were the basis for Dr. Hood’s (yes, doctor!!) rejection from Emory.

Dr. Hood went on to attend Loyola University Chicago Stritch School of Medicine. He was a practicing OBGYN and now is semi-retired working part-time at a clinic that treats patients regardless of their ability to pay.

His rejection letter is making the rounds on the Internet on this, the 59th anniversary, and it caused me to think. Lots of stuff causes me to think, but this got me thinking deeper.

“It’s a shame it took 60 years, but it’s moving in the right direction there are still barriers,” says Dr. Hood. “I don’t hold them personally responsible for what happened to me. They were just following the rule of the good ol’ South in those days.”

If you want to see Dr. Hood’s talk about why he got into medicine, click here: Georgia Man Reflects on Medical School Racial Denial on 59th Anniversary

I’m so, so grateful that race doesn’t matter to me, or most people, these days—despite what the news media and the loud voices on social media want us to believe. Are there racial and socio-economic barriers? Yes. Are things dire and bleak? I see progress.

I’m happy to receive the expertise of my healthcare providers regardless of what they look like. I’m much more interested in the makeup of their brains than the makeup of their skin tone. Only one of those body parts will save my life.

I got a jones to look up some facts and numbers about minorities and medical schools.

The first African American doctor graduated from a US medical school in 1847, also the year the American Medical Association formed. Two years later, in 1849, the first female graduated from a US medical school. Sadly, it wasn’t until 15 years later, in 1864, the first African American woman graduated. Her name was Rebecca Lee Crumpler.

Interestingly, today, African Americans still make up a smaller percentage of admissions into medical schools. White admissions have dropped in the last 35 years, but the only significant minority gain has been by Asians. Latinos have fared only a little better, but African Americans and Native Americans/Alaska Natives have not seen a significant increase in admissions.

Share This Story, Choose Your Platform!

Share This Story, Choose Your Platform!

Share This Story, Choose Your Platform!

Share This Story, Choose Your Platform!

Share This Story, Choose Your Platform!

Share This Story, Choose Your Platform!

Share This Story, Choose Your Platform!

Share This Story, Choose Your Platform!

The trickster tales suggested how the weak might outwit, deceive, or manipulate the strong. More broadly, they outlined the tactics and attributes necessary to cope with an irrational world where the good and the right did not generally prevail. They may have been escape valves for the pent-up frustration and bitterness of the slaves but they could also serve as cruel parodies of white society, exposing its pretension, hypocrisy, and injustice to ridicule.

There was an inevitable contradiction between the amoral strategy for survival recommended by the trickster tales and the standards and values taught by the moral tales or the spirituals. Religion, magic, folk beliefs, songs and spirituals, moral fables, and trickster tales were all part of the distinctive cultural style of the slaves. In particular, religion, family, and popular culture have been the focal points of the great outpouring of new work on the slave community since the 1970s. Blassingame has offered some intriguing speculations on status within the community. Those who were accorded higher status by the outside world–house servants, slave drivers, mulattoes–were often assigned a much humbler place by the inhabitants of the slave quarters. The slave community set its own standards, prizing above all loyalty and services performed for other slaves by, for example, preachers, conjurers, midwives, teachers, and in a different way, rebels. Occupations which took slaves away from the plantation or enabled them to earn money carried a certain prestige, and some special strength or skill–not least the cunning and resourcefulness to outwit the master or escape trouble–commanded a measure of respect in the community.

The broader evolution of African-American culture has been brilliantly explored by Lawrence Levine in his Black Culture and Black Consciousness. He sees in music and dance, song and story, rich evidence of the separate, independent life slaves lived alongside their existence of dependence upon their owners. Slave music was a distinct cultural form, created and constantly recreated through a blending of individual and communal expression. The sense of the oneness of things was reinforced by a firm belief, inherited from Africa, in a universe filled with spirits and luck who could be invoked, or for that matter provoked. Belief in magic and luck were valuable supports in a way of life as unpredictable and uncontrollable as that of the slave. Some were obviously tales with a moral, reinforcing religious beliefs and preaching the virtues of kindness, humility, family loyalty, and obedience to parents, and sometimes submissive or at least resignation, in the relation with the master.

Share This Story, Choose Your Platform!

African survivals in black American culture. The once widely held view that traces of the African heritage had been virtually extinguished in the Southern colonies and states has now been generally discarded. John Blassingame devotes the first third of his study The Slave Community to two long chapters. Blassingame and other historians have also pointed to the African influence on various artifacts, and the skills associated with them, in the South–for example, basket weaving, wood carving, pottery, the making of musical instruments, some architectural features, and many agricultural practices. “Cultural creolization” through which American ways were necessarily absorbed, but adapted, articulated, and understood with the aid of “African cultural grammars.” Joyner was writing of an area of great plantations, with perhaps the highest density of slave population on the North American mainland, where African influence was at its strongest. These special circumstances bred a distinct creole language, Gullah, the result of the convergence of a number of African languages with English. Clearly, many of the conditions of cultural creolization on the South Carolina sea islands were not replicated elsewhere.

Share This Story, Choose Your Platform!

Slave attitudes toward sex and marriage also have a curiously modern ring– for example in the relaxed view of prenuptial sex, the pattern of accepting several marriages, the normal presence of two working partners in a marriage, and an approach toward something resembling equality between the sexes.

It existed after all on the sufferance of the owner, and it was often shattered at his whim. Much of Gutman’s own evidence–whether on the forced breakup of marriages or the interference of masters with the domestic arrangements of their slaves–serves to emphasize this fundamental point. James Henry Hammond interfered in the family life of his slaves at every point, from naming of babies and the care and upbringing of young children to the encouragement of large families and the punishment of marital infidelity–though he did not lead by example in this latter respect. Like most masters, Hammond had a vested interest in the slave family as a means to the achievement of an enlarged workforce.

Gutman was the victim of his own eagerness to demolish the argument of other scholars. For all that, he established that the family was probably the most solid cement the slave community had. It was also uniquely important in that the family linked generations of slaves and their cumulative experience. It was the most powerful transmitter of slave culture. The culture (in the more specialized use of the term) which the family helped to transmit has itself been the subject of much discussion among recent historians.

Share This Story, Choose Your Platform!

There was no legal marriage for slaves, but “marriages” were widely recognized and served important functions for the slave community, as well as for the plantation. One-parent families existed in numbers and the maternal influence was everywhere strong, but the two-parent families predominated–even if it often included the offspring of earlier liaisons of one or both partners–and slave fathers carved out a recognizable role, despite all the difficulties. Sexual interference with slave women by white men was always a threat and often a fact. Such liaisons were occasionally voluntary, more often forced, usually casual, but sometimes enduring; there were rare instances of slave mistresses who virtually assumed the role of the planters wife. The double standards of a slave society were nowhere more apparent. Mary Boykin Chesnut, wife of a South Carolina planter, wrote mockingly that:

Like the patriarchs of our old men live all in one house with their wives and concubines, and the mulattoes sees in every family exactly resemble the white children–and every lady tells you who is the father of all the mulatto children in everybody’s household, but those in her own she seems to think drop from the clouds, or pretends so to think. Revealingly, she does not mention that slave families, too, had to live with the consequences of suc liaisons. The situation on another South Carolina plantation, that of James Henry Hammond, seems to have been quite bizarre. In an astonishing letter to his legitimate son, Hammond seeks to ensure that, after his death, good care be taken of two female slaves, mother and daughter, and their children. It emerges from the letter that both women have been mistresses of both the senior and junior Hammond, and there was more than a little uncertainty about which Hammond had sired which children!

The slave trade was the chief cause of broken marriages and divided families among the salves, but it did not break the institution of marriage and the family, of the belief in it. Perhaps as many as one-quarter or one-third of slave marriages were broken by such forced separation. Not all slave sales were a matter of unfettered choice or callous indifference on the part of the owner. Many resulted from debts, bankruptcy, and particularly the owner’s death, when his estate was often divided. The frequent movements of owners from one place to another was another common cause.

Share This Story, Choose Your Platform!

In complete contrast to Boles, and even to Genovese, Sterling Stuckey assigns religion a central role in the essential and virtually exclusive “Africanity” of slave culture. He expresses reasonable doubts about the proportion of slaves to ever actually took part in Christian worship, but commits himself to the extraordinary statement that “the great bulk of the slaves were scarcely touched by Christianity.” Elsewhere however, he takes a somewhat less rigid view and speaks of “the Africanization of Christianity,” or a “Christianity shot through with African values.” These would seem to be steps along the road to recognition of a genuinely African-American religion in which Christian and African influences interacted with each other or existed side by side. Indeed, he has some intriguing suggestions to offer about how the two traditions interrelate in practice, although he always insists on the primary of the African influence. In a typical passage, he discusses a ceremony common to Christianity and many West African religions; water immersion or baptism. He concludes that, as in most ostensibly, Christian ceremonies on slave plantations:

Christianity provided a protective exterior beneath which more complex, less familiar (to outsiders) religious principles and practices were operative. The features of Christianity peculiar to slaves were often manifestations of deeper African religious concerns, products of a religious outlook towards which the master class might otherwise be hostile. By operating under cover of Christianity, vital aspects of Africanity, which were considered eccentric involvement, sound and symbolism, could more easily be practiced openly. Slaves therefore had readily available the prospect of practicing, without being scored, essential features of African faith together with those of the new faith.

Clearly, not all the differences between the recent historians of Slave religion are reconcilable, but such an analysis, and especially its last entice, could form the basis of a widely shared understanding of the interaction of two religious traditions, if only one could dispense with the instance that the influence of one must always be subordinate to the influence of the other.

If religion supplied the inspiration, the family provided the environment in which slaves sought to create their own domain. Until quite recently, the idea that the slave family was a bastion of the slaves’ own life-style would have seemed palpably absurd. The overwhelming power of the master, the act of any legal status for slave marriage, the denial to the father of much of the normal parental role, the constant disruption of family life by slave sales, and the sexual exploitation of slave women by white men were generally assumed to have wrecked the chances of survival of anything remotely recognizable as family life. A new and very different picture has emerged from the work of Herbet Gutman, and from the vigorous response to Gutman’s work.

Share This Story, Choose Your Platform!

The services in a white rural Baptist or Methodist church, says Boles, had more in common with black worship than wish the dignified calm of a white Episcopalian service. With the exception of a few atypical areas with a very high percentages of blacks to whites, Boles thinks it likely that “in no other aspect of Black cultural life than religion had the values and practices of whites so deeply penetrated.” In a comparable observation, Blasingame estimates that “the church was the single most important institution for the ‘Americanization’ of the bondsman.”

For much of the colonial period, slave owners had serious doubts about attempts to convert the slaves to Christianity. However, the coincidence in the eighteenth century of the rapid growth of the slave population and community and the development of the Southern evangelical churches lead to a major change. In the nineteenth century, slaves became active members of Baptist and Methodist churches, sometimes representing a third or even half of the congregation. Boles claims that the churches were by far the most significant biracial institutions in the Old South, though he acknowledges that races sat apart in hurge, and that whites dominated the churches in every way that really mattered.

It is clear, too, that slaves took what they wanted and needed from their Christian faith and worship in its various forms. The emotional and psychological strengths which enabled slaves to withstand the dehumanizing aspects of their condition came in large measure from their faith For most slaves, says Boles, Christianity provided “both spiritual release and spiritual victory. They could inwardly repudiate the system and thus steel themselves to survive it. This subtle and profound spiritual freedom made their Christianity the most significant aspect of slave culture and defused much of the potential for insurrection.” But surely the faith of the slaves also kept alive the possibility of challenge to the system and the hope of deliverance.

Share This Story, Choose Your Platform!

What emerged from diverse traditions and the slaves’ adaption to the American environment was a distinct syncretic African-Christianity–and this development is traced more broadly by Blassingame and other historians. In a study of a very different South Carolina community, Orville Burton offers a rather different picture of the slave religion. He points to the revolutionary potential of some aspects of slave Christianity, notably in its emphasis on the theme of deliverance. But he also stresses the role of religion as an instrument of racial control in the hands of the whites. In his early efforts to assert his authority as a slaveholder, James Henry Hammond set out to break up black churches and stop black preaching, and urged his neighbors to do the same. He replaced the slave’s own meetings with regular white-controlled services, conducted by itinerant white preachers. But this was another battle where Hammond was unlikely to win a complete victory over his slaves; they continues to hold their own meetings, and Hammond remained fearful of the leadership and organization they provided in the slave community and of their potential challenge to his power.

The transformation in our understanding of slave religion achieved by Genovese, Raboteau, Levine, and others–like all such major reinterpretations–has aroused anxiety in those who fear that it may be pushed too far, and frustration in those who are anxious to press on still further. A leading member of the first school thought is John Boles, an acknowledged authority on the religious history of the South, who examines slave religion in this broader context.

In his view, the underground church with its worship conducted away from their masters has been “insufficiently understood and greatly exaggerated.” Boles does not deny the existence of the importance of religious activity within the slave quarters and among the slaves themselves, but sees it as an extension or supplement to a more public worship. According to boles, many more slaves participated in the worship of white or mixed churches than in their own private gatherings. The emotionalism, the style of preaching, and the active participation of the congregation, typical of black services had their parallels in Southern white churches. The services in a white rural Baptist or southern white churches.

Share This Story, Choose Your Platform!

As a general rule, slave labor was both intensive and extensive. Questions concerning the work of the slaves show how far the controversy provoked by Time on the Cross has helped to share the agenda for recent debate and further study, though few of the book’s conclusions remain unchallenged or unscathed. The work of genovese and others will almost certainly prove more durable, not least because it never loses sight of the interconnections between slave labor and many other aspects of the SOuth’s peculiar institution and the life of the slave community. Slave work is central to the study of slave society. It leads directly into consideration of even broader issues–on one hand, the overall efficiency and profitability of the SOuthern slave economy, and on the other, the quality of slave life, the nature of the slave personality, and the development of slave culture.

Share This Story, Choose Your Platform!

Negative nonpecuniary income is a remarkable euphemism; in plain language: it means that the work was unpleasant and unattractive to a degree which could not be overcome, in the eyes of free workers, even by large financial inducements. Whatever the inducements, free men would not voluntarily undertake work which slaves were compelled to do. In her biography of James Henry Hammond, Drew Gilphin Faust gives an account of one attempt to substitute free white workers for black slave labor. Both motives and the outcome were not exactly in accordance with the Time on the Cross model. Hammond was anxious to reclaim a large area of swap for agricultural development but feared the effect of work in such an environment on the health of his slaves. He therefore hired a crew of Irish laborers to undertake the work, but discharged them within three months because of their drunkenness and generally unsatisfactory performance. James Oakes tells of a Virginia planter who hired Irish laborers for similar unhealthy work. “A negro’s life is too valuable to be risked at it,” he said. “If a negro dies, it’s a considerable loss, you know.” At other times, Hammond occasionally employed local landless white as extra plantation laborers, but his view was that “white hands won’t stick,” and that their unreliability disrupted the plantation routine. There was clearly more to the relative advantages and disadvantages of slave and free labor than the calculation of “negative nonpecuniary income.

One other feature of slave work to which Fogel and Engerman refer is what they describe sa “the extraordinarily high labor participation rate” of the plantation work force. THis meant that “virtually every slave capable of being in the labor force was in it.” In the free labor system about one-third of the total population was in the work force. In the slave system, the proportion was two-thirds.26 “the extraordinarily high labor participation rate” is in fact another neutral sounding phrase which is euphemism for something extremely unpleasant. It means, in fact, that women and children, the aged and the handicapped, even expectant and nursing mothers, were all required to work. This was the consequence of compulsion, not of incentives. Moreover, they were made to work intensively, under constant supervision.

The basic element of fear on both sides of the master-slave relationship must never be forgotten. There remained an Awareness on both sides that Masters ultimately held sway over their slaves by force or the threat of force. It was this which set the limits within which everything else happened in slave Society. In some respects, especially in the religion and family Affairs, slavery was a kind of acknowledged, negotiated agreement, under which a party autonomous slave community emerged. These were probably the two most influential elements in the development of the slave community, and appropriately, both exemplify the ambivalence and the delicate balance which exists between the assertion of slave autonomy on one hand and the exercise of the Masters power on the other. In the pre-civil war decades slave-owners made considerable efforts, with the aid of the white preachers, to inculcate spiritual and moral values which would lend safety and stability to the peculiar Institution. Similarly, masters saw the family as an agent of discipline and orders, as well as of population increase. Whatever the designs and the vested interests of the masters, the slave community attached its own special significance to both institutions. Genovese places religion at the center of “the world the slaves made.” Kishos Christianity as a double-edged sword which could either sanction accommodation or justify resistance.

Blassingame has described the “hands-off” policy pursued by one Florida slave owner, and according to Theodore Rosengarten, one South Carolina planter, Thomas B Chaplin, took little interest in his slaves as individuals or in their family Arrangements. In his journal, he registered the births of slave children and also of his words. The only difference was that he named the horses’ sires but not the slaves’ fathers. More than half of the slaves in 1860 lived on plantations containing 20 or more slaves, it is obvious that only a small minority of Planter’s could personally supervise every detail of the work – let alone, one might add, the rest of the Slaves Life. As long as their work was not unsatisfactory and they refrained from serious misdemeanors, many slaves have little personal contact with whites and only occasionally have to act out the rituals of deference. Once again, must be emphasized that the situation on smaller farms and the relationship between small owners and their slaves were rather different.

The nationalism of the slave community was essentially African nationalism, consisting of values then bound slaves together and sustained them under brutal conditions of oppression. The centrality of the ancestral past to the African in America. Stuckey draws on material from slave songs, tales, rituals and ceremonies, and above all religion to build up his picture of the essentially African character of slave culture and to describe the process by which, as he sees it, people of diverse ethnic origins in Africa where fused in the New World into one African people. It is surely not possible to read completely out of the story the various influences of the American environment and the process of creolization. Stuckey himself has to admit the important role of the English language in bringing together slaves of diverse African backgrounds; he also acknowledged that some slaves were exposed to considerable white influence, but that they appropriated only those values which could be absorbed into their “Africanity”. Pleading that, for all its distinctiveness, it was a vital variant of the larger Southern Culture to which blacks contributed so much. Excessive claims for the “autonomy” of slave culture deny or belittle remarkable black achievments both in forging a distinctive culture and community life in the face of all the handicaps imposed by slavery, and in contributing so much to the development of Southern and indeed us culture. A modest but useful first step toward reducing these large portions to manageable proportions may be to turn to the day-to-day realities of the relationship between master and slave. There were10 blacks for every white in Jamaica in the early 19th century and 25 serf for every nobleman in Russia in 1858. The Southern slaveholders normally lived on the farm or Plantation, and slaves lived their daily lives surrounded by whites. The less acceptable face of the much discussed paternalism of the Southern slave system was its interventionism and constant inclusiveness. The drastic reduction of the level of independence in the antebellum slave community in such Basic matters as raising its own food or offering organized resistance in anything like a strike against the authority of the master. Unusually wide dispersal of slaves in ones and twos among various owners virtually forced the development of a social life beyond the individual holding. J. William Harris shows how, in an area of smaller forms in the Deep South where slaves were in close daily contact with their owners, the slave Community spilled over farm and Plantation boundaries to become a kind of wider, underground spiritual and social community. That broader community was nourished by religious services and the influence of ignorant creatures, by marriages between slaves of different owners, by the owners practice of lending their slaves to one another, and buy an underground network of social contacts and activities which the slave patrols were powerless to prevent, and to which Masters often turn a blind eye. Simply by counting heads and emphasizing the physical presence of many whites lnside the slave population, one minute exaggerated the degree, frequency, and directness of personal contact between owner and owned. Even on a small or medium-sized Plantation, which 15 or 20 or 30 slaves, the master may not always have known the slaves as well as individuals or taken much personal interest in them. Master saw a great deal of the domestic servants – although, like all classes who are accustomed to the presence of servants, owners and their families developed the ability to talk and act as if the servants were not there. However, the paths of the field hands and their masters – at least on the larger Plantation – may only infrequently have crossed. James Oakes insists that, while blacks and whites shaped each other’s Destiny, they did not do so through close personal contact mMutual understanding.

It is presumptuous in prosperity to dismiss contemptuously the methods that enabled generations of slaves to endure their harsh lot in life, and to snatch from it a few human satisfactions. It is tempting to assume that these subtle master-slave relationship, and the opportunities and the “space” it offered, must have provided fertile soil for the growth of slave community life and slave culture. One might take as examples the view of two white historians, one Southern and Northern, who have both written sensitively and sympathetically on black history. Joel Williamson restated the conventional, formative answer to the question of whether slave culture was largely a response to the impact of slavery itself. Most of what constituted Black Culture was a survival response to the world the white man made; most blacks had to shave their lives largely within the round of possibilities generated by whites. In sharp contrast, Herbert Gutman descended from such a view and charged most of the leading historians of slavery with complicity in his propagation. in which slave culture developed to the cumulative experience of generations and from the inner resources of the slave community. It was to some extent and adaptive process to the regards of slavery, but the form of that adaptation was shaped from within. He agreed with Sidney Mintz and Richard Price that African-American slave institutions took on their characteristics shape within the parameters of the masters monopoly of power, but separate from the masters institutions. Gutman criticized Genovese for his emphasis on the paternalistic compromise at the expense of the long and painful process by which Africans became Afro-American. Gutman came dangerously close at times to writing the slaveholders out of the story completely. Historian John Blasingame drew a distinction between the slaves’ primary environment, which they found in the social organization of their quarters, and their secondary environment, which centered on their work experience and the contact with whites that involved. It was the former, he insisted, which gave the slaves ethical rules, fostered cooperation, and promoted black solidarity. The large slice of the slaves’ waking hours which were taken up by their work may lead to speculation on how the work environment actually was. Indeed, earlier in his book, Blassingame offered a much more comprehensive explanation of the evolution of slave culture. It was not, he says, the contrast between the slaves African past and his dependency on the plantation which date remind his behavior, but rather the interaction between certain Universal elements of West African culture, the institutionalized demands of Plantation life, the process of enslavement, and he’s creative response to bon Bondage.

The Southern states would have ranked fourth in the world in 1860, behind only Australia, the northern United States, and Great Britain. But the crucial point is surely that it is the Northeast which enjoyed an enormous lead over the South, presumably because of its urban Industrial development. The danger, no doubt less discernible at the time then with hindsight, that the cotton bubble would burst and deprive the slave economy of its most conspicuous advantage. By 1860, the slaveholder was 10 times as well as the non slaveholder. Much of the explanation lay in the rising price of slaves. If one already own slaves, one could enjoy the benefit of the steady rise in their value; if one did not own slaves, it was increasingly difficult to get one’s foot on the first rung of the slaveholding ladder. It was the promise as much as the reality of upward Mobility that traditionally sustained the dreams of many non-slaveholding whites. The minute you put it out of the power of common Farmers to purchase a negro man or woman to help him on his farms, or his wife in the house, you make him an abolitionist at once. Slaveholders, and most nonslaveholders too, adhered to slavery above all because it was there, and they dreaded the consequences of its demise. “We were born under the institution and cannot now change or abolish it” said a Mississippi planter. You would have preferred to be “exterminated” rather than be forced to leave in the same society as the freed slaves. Slave and master when locked together in a system which the one could not escape and the other would not abandon.

In a valuable case study of one large planter, Drew Gilpin Faust has shown how James Henry Hammond was equally determined to transform his plantation into a profitable Enterprise and to protect himself as a beneficent master who would guide the development of those he regarded as backward people entrusted to his care by God. Oakes claims that, between the revolutionary era and the Civil War, whatever paternalist tradition existed in the South was overtaken and overwhelmed by the rising capitalist values of an expanding slave-owning Society of men on the make. Slavery became the basis of an increasingly paternalist social order – particularly after the ending of the external slave trade in 1808. Genovese argues that the early spread of European capitalism called forth a new system of slavery in the New World which in time proved incompatible went the consolidation of the capitalist World Order. Slave owners then assumed the mantle of the landed aristocracy in Europe by resisting the advance of the very capitalist system which had spawned them. The Old South was actually engaged in a process of rationalizing slavery, not only in an economic sense, but also in emotional and psychological terms. it would not be easy to demonstrate that it promoted the economic well-being of the non-slave-owning sections of the community – and the nonslaveholders were the large majority of the population. Slave ownership D provide a kind of escalator by which people might arise in southern Society, and Oaks has stressed that extent of upward (and presumably downward) mobility in Southern society and the frequency which individuals in and out of ownership of one or twoAlone but also other factors, such as the climate and the lack of adequate local markets, which hindered any movement toward diversification. Slavery did limit crop choices by enabling and encouraging Farmers to respond to World demand for cotton, by removing incentives to overcome the problems involved in growing other crops, and by helping to create an essentially rural economy and restricting the local market. The combined forces of cotton and slavery kept not only Southern agriculture but the whole Southern economy on the straight and narrow path which led to rejection of other choices and consequent retardation. The very success (and the profits) of plantation slavery and cotton cultivation removed any incentive to switch from agriculture to Industrial and Urban Development. In towns they could be replaced by white immigrant workers; on the plantations they were irreplaceable. In contrast, the South enjoyed the ephemeral advantage of being the dominant supplier of cotton to the World Market, a position which offered limited term enjoyment of profit not necessarily linked to real efficiency, but not the long-term prospect of sustained growth. In slavery the near-paradox of an economic institution competitively effective under certain conditions, but essentially regressive in its influence on the socio-economic evolution of the section where it prevailed. While the South expanded along one line, the North was branching out in many new directions.

If paternal list owners as to assumed responsibility for their slaves, they also strove constantly to maintain and reinforce the utterly dependent status of those slaves. The accumulation of land and slaves was the prime motive, perhaps even the obsession, of nineteenth-century slaveholders, but it regards this as proof that they were a class of acquisitive entrepreneurs and capitalists, dominated by a metrolist ethos and dedicated to free-market commercialism. The intense pressures in southern white Society toward material success and the ownership of more and more slaves was regarded as the yardstick of that success. Genovese and Oaks are powerful and articulate recent protagonists in a debate which has continued for half a century or more about the nature of southern slave society.

The choice of priorities facing Southern farmers and Planters was between but sweet of Maximum profit, with the attendant risks, and the achievement of Greater security by concentrating first on substance subsistence farming, and then in addition growing some cotton for cash. Northern counterpart, whose cash crops, such as wheat were also Food crops. However hard the times, the southern farmer could not eat cotton or feed it to the Hogs. It is surely impossible to make if fear and Illuminating comparison between a large-scale planter with 50 or a hundred slaves producing cotton for export, and the characteristic Northern Family Farm employing little if any labor outside the family and producing a variety of cereal and animal products, with the prospect of selling any surplus on the open market. The two operations are different in scale, structure, and purpose – and in their social and economic context. Comparison between southern slave labor and Northern wage labor is not possible and not valid historically – because there was hardly any wage labor on Northern Farms. The answer lies in the chronic and desperate shortage of farm labor for hire in the North and Northwest. Land was abundant, and most men aspired to be Farmers rather than Farm Workers. The size of the family farm was limited by the amount of Labor the Family itself could provide. In the south, the presence of slavery altered the whole position semi the farmer or plantar could parties as many slaves as financial resources permitted.

Beneath the overseer in the hierarchy were the slave drivers, men drawn from the ranks of slaves themselves and often taking responsibility for much of the day-to-day running of the plantation. On smaller plantations, where no overseer was hired, the slave driver was often in a position of authority if, for example, the master was absent.

The slave driver occupied a position which was prestigious but precarious. He was put in a position of trust by the master and enjoyed certain privileges and prerequisites; but always he had to be sensitive to the feelings of his fellow slaves, among whom he may have enjoyed a measure of respect but in whom he could all to easily inspire jealousy and resentment.

How hard did slaves in fact work?

The view which prevailed for many years was that slaves worked long and hard simply because they were forced to under threat of the lash, but that they achieved no high level of efficiency. In relative terms, low efficiency was made tolerable by the low cost of slave labor.

role of incentives- a garden plot, permission to sell produce from it, extra holidays or passes to leave the plantation, and even money payments and crude profit-sharing schemes. But he sees incentives as but one weapon- and a subsidiary one- an armory of slave control which included firm discipline, demonstrations of the master’s power (symbolized by the whip), and the inculcation of a sense of slave inferiority.

Far from being lazy or incompetent, slaves were, they argued, more efficient and industrious on average than their free counterpart.

Every 1 percent increase in the cotton share was accompanied by a 1 percent increase in the output per worker. When output is valued at market prices, cotton comprised about one quarter of the output of typical sleeveless farms, but three-fifths or more for the largest slaveholding cotton plantations. Cotton amounted in 1850 to only one-quarter of total Southern agricultural output, and tobacco, sugar, and rice together to less than another 10 percent. The largest Southern crop was not in fact cotton but corn, which was cheap to grow, and, very conveniently, could be both planted and harvested at times different from cotton. Among other things, Provided food for livestock, notably Hogs and the South had 2/3 of the hugs in the United States in 1860 the consequence of the compatibility of cotton and corn production was to make the South virtually self-sufficient as far as food was concerned (although there where local imbalances).

Slaves as well as freemen rested on the Sabbath. There were times, too, when bad weather or the season of the year relieved the burden of work the field hands shouldered. The peak demand for labor came at the end of the season, at cotton-picking time, when every available hand, whatever his or her normal occupation, was needed in the fields. Indeed the productivity of the cotton plantation was limited more by this bottleneck at the point of picking than by the work rate or efficiency of the slave labor force throughout the year. The Old South had the capacity to grow more cotton than it could pick, and until that problem was solved, there was little incentive to mechanize or modernize the earlier stages of cotton cultivation.

Plantation slaves were classified as full or fractional (half, quarter, etc.) hands, with the old, the younger children, and the expectant and nursing mothers regarded as equivalent to something less than a full field hand. Slaves who were not working in the fields were full-time or part-time domestics, craftspersons, mechanics, gardeners, blacksmiths, carpenters, millers, seamstresses, or general workers. Skilled workers were often important figures in the work of the plantation ad in the life of the slave community. Household staff on some of the grander plantations were sometimes encouraged to give themselves a few airs and graces, but elsewhere the distinction between domestic servants and field slaves was much less clear-cut. A maid in the big house might share a cabi with a field-hand husband and their children. At peak times, domestic slaves were often required to work in the fields.

The organization and supervision of a substantial slave work force demanded considerable managerial skill.

there was often a world of difference between the ideal as expounded in print and the reality as it practiced amid all the vagaries of weather, pestilence, fluctuating prices, and irrepressible humanity of the owner’s slave property. On plantations large enough to justify such a management structure, the master would employ an overseer, usually white but occasionally black, who bore a considerable load of responsibility and shielded the owner from some of the more tedious and unpleasant aspects of slave ownership. The overseer was very much the man in the middle, under pressure from the master and often unpopular with the slaves. Required to maximize the crop while dealing fairly with the slaves, he lived from one insoluble dilemma to the next.

“I have no overseer,” wrote one farmer, “and do not manage so scientifically as those who are able to lay down rules; yet I endeavor to manage so that myself, family, and negroes may take pleasure and delight in our relations.” Not all small owners shared such similar disposition or similar priorities, and the slaves of such owners were, more directly than most, at the mercy of the moods and whims of individual masters.

It was the great planters, after all who left the most substantial historical record. There is inadequate information, too, about slaves belonging to what Oakes calls the middle-class owners. However, some historians- Paul Burton and Orville Burton, for example- incline to the view that such slaves probably experienced some of the harshest working conditions. They suffered from the worst of both worlds: They lacked on one hand the close working relationship with the owner of a small farm, and on the other hand the security, order, and sense of belonging to a sizeable slave community provided by the larger plantations.

Among plantation slaves, around half were normally full-time field hands, although efficient owners were always striving to increase that proportion. The relentless routine of the seasons required more labor in the fields at some times, less at others. On cotton plantations, the hoe was the main implement in the hands of gangs of field hands as they toiled in the sun under regular supervision to clear the grass and weeds which always threatened to overwhelm the cotton plants. Some planters preferred the task system to the gang system, particularly in rice-growing areas. Under this system, each hand was assigned a task for the day and could stop work early when he or she had completed that task.

James Henry Hammond tried to abolish the task system on his South Carolina plantation, but pressure from his slaves obliged him to restore it at least to a modified form.

Working hours were long- traditionally from sunup to sundown- but recognized breaks during the day were generally observed.

The great majority of slaves were employed in agriculture, or in occupations relating to it. Most worked on the cultivation of the great staple crops of the South. The census of 1850 offered estimates which may be little more than reasonable gays all of the numbers employed in the production of the major crops. Out of 2.5 million slaves directly employed in agriculture, it calculated that 350,000 we’re engaged in the cultivation of tobacco; 150,000 in Sugar; 125,000 in rice; 60,000 in hemp; and a massive 1,815,000 cotton. The working life of the slaves of smaller owners was not in many respects very different from the lot of the farm laborer elsewhere.

The picture of slavery is largely borne out by James Oaks’s study of Southern slaveholders, The Ruling Race. He divides the slave Owners broadly into three categories. At one extreme were the small Elite of great planters who have commanded so much of the Limelight in both Southern mythology and Southern historiography. At The Other Extreme was the large number of owners of no more than five slaves. Members of this group commonly worked alongside their handful of slaves in the fields and shared with them the ups and downs of their lives, they’re generally precarious economic situations, and their frequent Moves In Search of a fresh start. Between these two contrasting classes of large Planters and small, struggling former what does substantial numbers of middle-class Masters, Oaks sees a very much the backbone of southern slave Society. Then we’re often ambitious, upwardly mobile men, constantly seeking to acquire more land and more slaves, and often combining their land ownership with pursuit of other business or professional interests, as shopkeepers, Artisans, doctors, teachers, and, most notably perhaps, as lawyers.

Four members of all three classes, slave ownership was an indication of status and a vehicle of upward Mobility. But they invested in slaves, and yet more slaves, chiefly for the labor, and it is appropriate that any more detailed consideration of the South’s peculiar institution should begin with the work slaves were required to undertake. Before all else, a slave life was one of toil.

In 1860, 29 of the 88 Southern slaveholders who owned more than 300 slaves were rice planters. No fewer than seven of them on plantations on the Waccamaw. At the very apex of slave ownership were the 14 men who owned more than 500 slaves; nine of them were rice Planters, and three of those planted on the Waccamaw. one of those three, Joshua Ward, was the only planter in the whole South who owned more than 1,000 slaves. One quarter of southern white families owned slaves in 1860 is a neutral and objective statement of fact. If attention is confined to the states that eventually became part of the Confederacy, 31% of white families owned slaves in 1860. In South Carolina and Mississippi, almost half the white families owned slaves; in four more states of the Deep South, 1/3 or more of the white families owned slaves. The fairest kind of comparison, he argues, is with other forms of property ownership in other periods. For example, in 1949, only 2% of American families held stock worth $5,000 or more – roughly equivalent in today’s terms to the worth of one slave. No doubt by the 1980s the percentage will have increased considerably, but not to the point where it would come anywhere close to the figures for slave ownership in the Old South. “Slavery” says Olsen, “appears a good bit less oligarchical in several significant economic respects 20th century free labor capitalism. The ownership of slaves were spread among a remarkably broad proportion of the white population, and the extent of this investment was Central to Southern White Community before, during and after the Civil War.

At the summit of the Southern social pyramid where the 10,000 owners with more than 50 slaves, including 2,000 with more than 100. The majority of slaveholders are there for small-scale owners, but large-scale ownership by a small minority meant that more than half the slaves lived on plantations with more than 20 slaves. John Boles has pointed out the interesting statistical coincidence that, in 1850, 72.4% of slaveholders owned spent in slaves, but at the same time precisely 73.4% of slaves lived in units numbering more than 10. Behind all the census figures lies the fundamental but often forgettable fact that three-quarters of southern white families owned no slaves at all. Numerically at least, the typical white Southerner were small farmers cultivating their own soil, not infrequently on the move from one area to another, and in many respects not unlike their Northern counterparts, except that they lived check-by-Jowl with slavery and accepted its social and racial imperatives as well as its economic repercussions. the other side of this coin reveals that the great Plantation owner with his hundreds or at least scores of slaves – it figures so Central to the legend and the Romance of the Old South – belonged to a tiny minority of the white population. The plantations of many of the largest slave owners cultivated, not cotton, the Great Southern State, but either sugar, in Louisiana, or rice, on the coasts and sea Islands of South Carolina and Georgia.

The census of 1860 showed that there were nearly four million slaves out of a total population of 12.3 million in the 15 slave states. The proportion of slave to white population very gritty from area to area, with the heaviest concentrations in the Deep South. In South Carolina and Mississippi more than half the population were slaves, and in Louisiana, Alabama, Florida, and Georgia the slave population was more than 2/5. In no other state did slaves amount to one-third of the population; in Maryland, the proportion was 13%, in Missouri 10%, in Delaware Amir 1.5%. Overall, there were some 385,000 slave-owners out of about 1.5 million white families (and a total world population of 8 million).

The spread of cotton cultivation was accompanied by a large-scale movement of slaves, often over long distances, the new lands of Alabama and Mississippi. Since the revolution, there had already been considerable movement of slaves from Virginia into Kentucky and Tennessee, much of it in groups as owners moved Westward, taking their families and their slaves with them.Longer – distance migration to the Southwest encouraged the development after 1815 of a more organized slave trade, which was much more destructive in its effects upon the slaves, and particularly upon their families. It almost tripled in the decade after the war of 1812 – both the area of slavery and the number of slaves also grew rapidly. In anticipation of that event, something like a hundred thousand slaves from Africa were brought into the United States between 1790 and the ending of the tread – and almost 40,000 of them arrived at Charlestown alone in the last few years before 1808. It was conclusively demonstrated that the natural increase of the slave population would be able to sustain the continued expansion of the slave South. By 1830, the number of slaves had passed the 2 million mark. This capacity for growth and potential for further growth were the most astonishing features of the whole period.

Slavery was flourishing as a labor system, a social institution, and the device for control of one race by another. It was a system which lived on, bye, and with fear. Slaves were compelled by force of circumstances to fear their masters; non-slave-owning whites felt threatened socially and economically by blacks, what does slave or free semi color and all Southern whites shared the constant, nagging fear of servile Insurrection – and, in 1831, the Nat Turner Uprising in the Southampton County, Virginia, fed that fear anew. The whole wide South feared outside interference or domination. Parts of the upper South and the Atlantic Seaboard feared for the future of slavery on their exhausted or depleted soils. Slave owners generally feared for their social status, their economic well-being, and their personal security, should their peculiar institution come to an end., the fear which subsumed meaning of the others was dread Consequences economic ruin, social chaos, and racial Anarchy – which, it was generally believed, would follow the abandonment of slavery.

Two prominent features of Southern slavery conspired to add to the paradoxes of the system. First, slavery was explicitly and essentially ratio. The line of race and color drawn between master and the slave was so firm that the few exceptions did not threaten it. This line dictated the formal rigidity of the Master-slave relationship, the difficulty and lifting Rarity of manumission, and the Twilight existence of the free black community. There were few Escape hatches of any kind, and the color of a slave’s skin marked him or her indelibly. bondage was a life sentence and a hereditary one. Stanley Elkins attributes the harsh lines and severity of the slave system to its origins in “unrestrained capitalism”. Racism, at least as much as capitalism, may have been the villain of the piece, and the one no doubt reinforced the other.

The free black population of the South multiplied several times over between 1776 and 1800, but even in the Chesapeake Bay Region it was still very heavily outnumbered by the slave population. The city of Baltimore was the only place in the region where there were more free blacks than slaves. With hindsight, it is possible to see the beginning of the process which would eventually make Maryland as much a state with free black as a slave state, but as Richard Dunn has observed, the experience of Virginia was very different. There, during the early. Of the United States, slavery was still expanding and strengthening its grip.

Paradoxically, the new expansion to place within limits which were themselves been defined with increasing sharpness. It is true that the wave of post-test Revolution manumissions soon subside, and legal and social pressures discouraged further resort to them. but, if constraints within the South weekend, restrictions imposed from outside gained strength during the following decades. In the North, where slavery had more much shallower Roots, the awkward question raised by the ideology of the Revolution found a more receptive audience. During or after the revolution, the northern states all committed themselves to the abolition of slavery, although the process was painfully slow in some cases.

The Northwest Ordinance of 1787 kept slavery out of the vast territory to the north of the Ohio River, although for more than 30 years attempts were made to break down the barrier. The stage was set for the parallel and completitive expansion of freedom and slavery into the Great Central Valley of the United States. In 1820, the Missouri Compromise Barb slavery from most of the huge Louisiana Purchase and, in fact, left slavery with little further scope for expansion in the remaining territories of the United States as they then existed. It’s about the ability of Supply to keep Pace with demand for slave labor were raised by the ban on the importation of slaves imposed in 1808. The Constitution had prevented any such ban before 1808, but Congress lost no time in acting once it had the Constitutional authority to do so.Mass movement of slaves into the deep south and the Southwest sowed the seeds of slavery’s relative decline in the upper South. By the 1830s the rising Abolitionist Movement in the north added moral strictures to the territorial restrictions of slavery.

External moves to circumcise slavery, actually was given a new lease on life during the same period. It’s Westward surge shifted the whole center of gravity of the South’s peculiar institution dramatically from the upper South to the Deep South and from east to west. The key to that expansion lay in Cotton. In the agree culture of the colonial South, cotton was a very minor crop indeed semi color in the generation after 1790, it came into power in the southern Kingdom. Demand, technology, land, and labor came together to launch the cotton boom. The demand came from across the Atlantic, above all from Britain, what did The Logical Innovation put cotton Mills in the Forefront of the Industrial Revolution. Southern ability to meet the demand dependent on another, and simply are, technological development – the cotton gin. With the removal of the Native Americans from large areas, South Carolina and Georgia became the first major Cotton States; but, particularly after the war of 1812, settlement poured onto the rich soil of the black belt in Alabama and Mississippi, which became the heartland of the cotton Kingdom. Slave labor supplied the other necessity of the expanding Realm.

All of the Revolutionary generation managed to retain both their philosophy and their peculiar institution of slavery by redefining the humanity of the Negro. The free Society of the infant republic was an even more consciously and explicitly White Society than its colonial predecessor. In 1790, the first federal census counted over 650,000 thousand slaves in the southern states – a sizable element in a total US population of less than 4 million.

Concerned themselves predominantly with the working lives of their slaves and we’re often content to ignore the slaves’ other life, which went on in the quarters after working hours or on days of rest. Place where more than passive observers are victims of the war of independence. Both sides used them as Frontline soldiers, or more often in a variety of ancillary rules; much the larger numbers were engaged on the British side. Many slaves opportunities for seeking individual Freedom during the Revolutionary War, and as many as 50,000 may have been evacuated with the British forces in the closing stages – although some later returned.

Among slave Imports, there had always been a preponderance of males probably at least two males for every female. Whatever the precise combination of factors at work, the beginnings of a sustained natural increase transformed the future prospects of slavery in the South. Slaves imported directly from Africa often struck their owners as more alien than earlier arrival from the Caribbean, and therefore in need of much tighter control. On the other hand, as the numbers of the American dashboard increased, Masters found themselves dealing with the slave population which had known no other life but slavery, and habits of submissiveness could be incilcated from infancy.

Most convincing explanation, offered by Winthrop Jordan and others, is that the institution of Chattel slavery and the clear belief in the racial inferiority of the African marched hand-in-hand, with each supporting and reinforcing the other. The assumption that the distinction between freedom and servitude must always be clear and ambiguous flows naturally from the attitudes and social structure of modern Western Society. However, things looked very different in the more hierarchical European Society, shaped by the presence or the legacy of feudalism, from which the settlers came.

It was the Portuguese and the Dutch who dominated the trade for a long period. It is impossible to be precise, but in the four centuries between 1450 and 1850, over 10 million – perhaps near 12 million – slaves were transported from Africa, but only just over half a million (less than 5% of the total) were imported into areas which are now part of the United States. Jamaica, Cuba, and Haiti each imported many more slaves than the whole of the North American mainland. It is one more of the paradoxes of Southern slavery that the smallest importer of slaves into the Americas should by the 90th Century have the largest slave population. Blacks were part of the beginnings of American history, but their numbers remained very small throughout the nine 17th century. For 50 years at least, they were counted in hundreds rather than thousands, and even after a sport in the closing years of the century they totaled only 26,000 in 1700, 70% of them in Virginia and Maryland. For much of the 17th century, there was probably easier and more informal social contact between whites and blacks, at least at the lower end of the social scale, then in most later periods of American history. The most convincing explanation, offered by Winthrop Jordan and others, is that the institution of chattel slavery and the clear believe in the racial inferiority of the African marched hand-in-hand, with each supporting and reforms reinforcing the other. The exemption that the distinction between freedom and servitude must always be clear and unambiguous flows naturally from the attitudes and social structure of modern Western Society. However, things looked very different in the more hierarchical European Society, shipped by the presence or the legacy of feudalism, from which the settlers came.

Chesapeake settlements were founded in the expectation of relying upon white labor of one kind or another – and Tobacco, which son became the staple crop, did not request slave labor in the way rise or, later, Cotton would. A decline in the English birthrate and the opening up of new colonies to the north of Maryland and Virginia reduced the supply of indentured servants. possibly for the first time in American history, but certainly not for the last, greater instance of black inferiority was seen as a means of reducing tension among whites.

South Carolina was virtually a transplant from the Caribbean, particularly the Barbados, and its population included a substantial black element from the early days. The climate was not encouraging to White labor, and once rice cultivation developed in the 1690s, Are swell even more in demand. Their skills and knowledge made a crucial contribution to the rice culture of Carolina low-country.

Half century before the American Revolution was it of consolidation and the enforcement of what was now it firmly based slave system. Slavery’s geographical spread was quite wide in the South, and even in the north, but it’s real numerical strength and economic and social importance we’re still concentrated around its two main Atlantic Bridge heads, the tobacco that’s growing area of Virginia and Maryland and the subtropical rice and indigo region of South Carolina and Georgia. This was the period when many of the enduring and distinctive features of Southern slavery assumed they’re recognizable shape.

Photos of revolutionary cause succeeded either in compartmentalizing their thinking, so that the Republican Liberty’s of whites could be kept distinct from the emancipation of enslaved blacks, or introducing the problem to one of priorities and assigning to emancipation a rather low place. The conservative phase of the Revolution showed in a profound respect for property rights, which included property rights in slaves, and in an abiding fear of upsetting the delicate mechanisms of slave Society. Americans of the Revolutionary generation managed to retain both their philosophy and their peculiar institution of slavery by defining the humanity of the Negro. The free Society of the infant Republic wasn’t even more consciously and explicitly White Society than its Colonial predecessor.

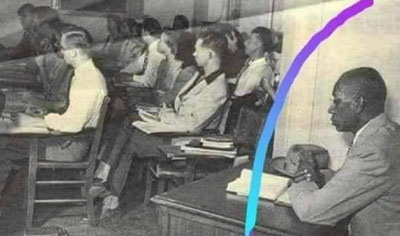

George McLaurin, the first black man admitted to the University of Oklahoma in 1948, was forced to sit in a corner far from his white classmates. But his name remains on the honor roll as one of the three best students of the university. These are his words: “Some colleagues would look at me like I was an animal, no one would give me a word, the teachers seemed like they were not even there for me, nor did they always take my questions when I asked. But I devoted myself so much that afterwards, they began to look for me to give them explanations and to clear their questions.” ©African History

Slave traders openly discussed their business-documents, financing, and bribes-while dining at their favorite restaurant, Sweet’s, on Fulton Street.

Goods on credit in anticipation of the next year’s crop,” and “it is equally well known” that Northern merchants supplied the credit. The North provided commerce, the South provided cotton.

Southerners sought financing in New York for their railroads, mines, and other expensive project.

When Southern planters defaulted, New York financial backers had to take possession of slave collateral.

Everyone knows that the planter receives……………

What became known as the cotton triangle? The points of the triangle were New York, Liverpool, and ports in the South, including Charleston, Mobile, and New Orleans.

When the Founding Fathers severed ties with England and took stock of their tattered collection of newly declared “states,” they longed for a means of creating a unified nation. None of them could have imagined in its development. But by the late 1850s, dependence on cotton money gave enormous clout to Southern secessionists, and contributed to the coming of war.

New York was the nineteenth century hub for much of American’s commerce, and cotton was no exception. A look at New York’s role in the cotton trade reveals fascinating alliances and deep bonds between North and South, built on profit and personal relations. Sothern’s claimed, with a certain changing, that 40 percent of all cotton revenues landed in New York.

That “flock of down” was cultivated by millions of black slaves whose value rose with the price and power of cotton. By 1860 the approximately four million slaves in the United States were estimated to be worth $2 billion to $4 billion. The aggregate value of the slaves was calculated by multiplying the number of a slaves by a representative price for each age, gender, or occupation category. But caution should be observed when interpreting slave wealth or capital, Except for periods of excess, the price of a slave was vulnerably suspended over the price of cotton. And if a sizeable number of slaves were offered for sale, the price would plummet. The paper calculation of slave wealth was thus a static number in a dynamic environment. Planters could not sell their slave unless they had an alternative labor source. So the $2 billion plus figure is not accurate in calculating market value. In the long run the slave was worth only as much as the profit or expected profit that could be produced from his or her labor. After the Civil War, because cotton production still generated revenue, it could still be financed.

In addition to its profits, cotton was king because it helped create Southern bombast and inspired rhetoric about slavery and an expanding slave reprice, Jefferson Davis, during discussions about California’s entry a free of slave state, was influenced by the Gold Rush in 1849-1850. He blandly promoted slavery, “I hold that the pursuit of gold washing and mining is better adapted to slave labor than to any other species of labor recognized among us.” Southern other than Davis spoke and wrote of mining ventures in Mexico, Chile, and the American West. Sell others dreamed of dominating a slave-based empire that would include the traditional staple of sugar in Cuba and Mexico.

The Most ambitious plan emanated from Dr. David Livingstone, the Scottish missionary turned explorer. Livingstone wanted to replace American cotton with African cotton produced by free labor in Batoka. His “bold messianic vision linked together not only ecommerce, civilization and Christianity but also free trade free labour.” Nothing came of these plans to displace American cotton.

The English press grew alarmed about this dependence. Blackwood’s Magazine in 1853 bemoaned the fate of “millions in every manufacturing country in Europe within the power of an oligarchy of planters.”

Cotton was unique; it maintained a clout that slave-produced sugar never commanded. The British anti-slavery organization, the Society of Friends, had employed a boycott of sugar in its assault on slave-grown West Indian sugar. In the 1790s an estimated 400,000 British boycotted this sugar, and sugar imports from Indian increased. But the gesture had a negligible impact on the sugar plantations. Even a symbolic boycott or attack on American slave-produced cotton was impossible. American cotton was far more difficult to replace than sugar grown by slaves thousands of miles from Britain.

Britain, aware of its precarious dependency on American slave-grown cotton, was not concerned about. American slavery, it feared a civil war or crop failure in America, which might be devastating. In 1858 the Lancashire mills established the Cotton Supply Association, with the specific purpose of diversifying sources for cotton to India, Egypt, and Brazil.

Thought that the American North and Great Britain depended on cotton. In 1858 the South produced 66 percent of all U.S. exports. In 1859 the Northern exports were $45 million compared to $193 million from the South, of which cotton accounted for $161 million.

Cotton revenues allowed American to develop her nascent industries and provide a basis for monetary affairs. In 1860 the Northern cotton textile industry led America’s other manufacturing sectors. Northern cotton mills manufactured goods valued at $115 million, “against $73 million for wool, and an almost equal amount for forged, rolled, wrought, and cast iron taken together.” Southern slave-grown cotton was responsible for the cheap raw material that fueled the Northern mills. Cotton yielded the revenue to enable the South to buy goods from Northern merchants.

Cotton dominated the American export market from 1803 to 1937 and played the leading role in the dynamic economic growth of the antebellum period. As the business historian George David Smith wrote.

Never before, and certainly not since, has the demand for any one crop fired economic growth to the degree that cotton did in the United States during the five decades before the Civil War. Without cotton, that growth would have far less dramatic.

The South’s slave–produced cotton exports were the backbone of its power and sense of nationhood. It was easy to see why the South…..

Slavery could never survive in a climate of marginal profitability.

The union of cotton and slavery was never successfully challenged by other enterprises. Southern manufacturing and mining enterprises could not compete with cotton for slave labor. Efforts to use slave labor in industry in the early part of the nineteenth century succumbed to the price of cotton, as the upward surge of cotton prices-from ten cents a pound in 1838-drove slave value higher. Slave were more valuable in the cotton fields than elsewhere.

Another theoretical means of avoiding Northern control was allegedly simple: diversify away from cotton. Journals and conventions urged the development of railroads, financial institutions, manufacturing capacity, and production of foodstuffs.

New England and Old England, by their superior enterprise and sagacity, turn it chiefly to their advantage.

Dependence in Northern capital was a degrading feature of the cotton economy, which operated on credit held by Northern banks.

The cotton states-South Carolina, Georgia, Alabama, Tennessee, Mississippi, and Louisiana did not reach North’s 1837 level of $105 million in loans outstanding even by 1860. Southern wealth was tied up in slaves and land and hand little capital for other purpose. Southern knew they paid almost 90 percent of the country’s tariffs because of the South’s dependence on imported manufactured goods, which were taxed.

The South depended on cotton; cotton depended on salary.

The American government relied on tariff revenues generated by the South.

Indeed, revenues from land sales and tariffs had allowed the government to eliminate the national debt. He further extolled cotton’s impact on “the prosperity of the south, on the rise in the value of their slave property, and on the great profits yielded by all… [the] capital invested in growing cotton. ”

In 1836, Treasury Secretary Levi Woodbury confidently explained the “preeminence” of American cotton trade. He believed that American would remain dominant because of “good cotton land enough in the United States and at low prices, easily to grow, not only all the cotton wanted for foreign export……., but to supply the increased demand for it, probably for all ages.” Despite “great vibration,” the price of cotton would sustain “great profits” for capital invested in cotton production. The crux of his argument was price:

The single fact, that in no year has the price been but a fraction below 10 cents per pound, or at a rate sufficient to yield a fair profit, while it has, at times, been as high as 29,34, and even 44, and been on average, over 16 cents per pound since 1802, and over 21 since 1790, is probably without parallel, in showing a large and continued profit.

As Woodbury noted, the price fluctuation had influenced “the sale of public land and our revenue.”

America was plagued by periodic financial and economic debacles during the nineteenth century. Serious crises occurred in 1819, 1837, 1857, 1873, and 1893. The Panic of 1837, in particular, jarred American society and illustrated the central role of cotton.

The decade of the 1830s was central to the ascendancy of the cotton economy, with more than twenty million new acres made available in the cotton-growing states. The expansion was financed by capital from the North and from Europe, and cotton, in turn, became the critical underpinning of America’s ability to borrow money. European capital flowed to America because of its financial system, cotton exports, and perceived investment opportunities. From the beginning America had depended on foreign capital and in particular on European banks, which had extended the new republic $130 million in loans to finance American businesses, canals, and railroads. All the Eire Canal bonds….

After Johnson shipped his cotton on the Mississippi River to New Orleans, a series of several transactions that involved both U.S. dollars and British pounds sterling took place, with risk involved at each stage. The cotton was exchanged for negotiable receipts or bills backed by cotton. These instruments were traded in New York, Boston, Philadelphia, Liverpool, London, and elsewhere.

In the 1820s became the world’s largest cotton exporter.

The Dred Scott case (1857) was the most famous legal opinion involving slavery. Scot, a Missouri slave, accompanied his owner to live in the free states of Wisconsin and Illinois for several years. Upon returning to Missouri, Scott sued for his freedom. The U.S. Supreme Court held that a slave “had no rights which the white man was bound to respect.” In other words, a slave was not a citizen.

In 1834 she married the profligate South Carolinian Pierce Butler, the second largest slaveholder in the state.

Kemble was comforted that the sale would provide financial security for her daughters. Her biographer reported that she “grieved over the upheaval the Savannah sale would surely visit on the unfortunate Butler slaves, even as she counted on the proceeds to bring an end to her daughter’ poverty. ”

Isaac Franklin, in New Orleans. The firm owned four ships-the tribune, United States, Isaac Franklin, and Unease-that transported slaves and other passengers from Virginia to New Orleans. It encouraged passengers, who were often planters, to inspect the slave quarters and assess the “merchandise.”

Public slave auctions were regulated by the same credit and commercial laws that applied to other businesses. Before the Civil War, slave sales constituted “one sixth of the nearly 11,000 American appellate cases involving slaves.” Disputants sought remedies and were generally concerned with “transfer and protection of property rights, not with the established of ownership.” Southern courts deemed sales to be “contractual right and responsibilities agreed to by buyers and sellers.” Judges encouraged participants to “develop standardized forms of dealing.”

The cash generated by the slave-trading process was a powerful incentive even for anti-slavery advocates such as the English actress Frances Anne (Fanny) Kemble.

Franklin & Armfield, the largest of the slaves trading firms, began in 1824. John Armfield purchased slaves at his base in Alexandria, Virginia, and sold them to his partner,

Slave trading was conducted with all the trappings of ordinary business procedures –public advertising, credit, legal rules and recourse, and open auctions. New Orleans was the largest auction market, but in big cities and small towns across the cotton south, public of demand were common.

When an Irish worker contracted fever and died in the swamps, he was buried; when a slave died, the “contractor” had to pay his owner as much as $900.

Twenty percent of slaveholders owned only one slave; 99 percent owned fewer than 100. In 1860 only 14 “millionaire” planters held more than 500 slaves.

By the 1850s, idealistic Northerners like Frederick Law Olmsted thought that free white labor could replace slave labor in the growing of cotton. Olmsted used the example of successful German immigrants who were raising cotton in Texas in the 1850s.

Olmsted’s naïve analogy disregards the inherent risk factor and once-a-year cash flow that made cotton farming unsuitable for corporate capital structures. Planters used land slaves to collateralize loans; additional borrowings were predicated on selling crops.