(Excerpt from The Gospel Truth about the Negro Spiritual, by Randye Jones)

A Brief History

Negro spirituals are songs created by the Africans who were captured and brought to the United States to be sold into slavery. This stolen race was deprived of their languages, families, and cultures; yet, their masters could not take away their music.

Over the years, these slaves and their descendants adopted Christianity, the religion of their masters. They re-shaped it into a deeply personal way of dealing with the oppression of their enslavement. Their songs, which were to become known as spirituals, reflected the slaves’ need to express their new faith:

My people told stories, from Genesis to Revelation, with God’s faithful as the main characters. They knew about Adam and Eve in the Garden, about Moses and the Red Sea. They sang of the Hebrew children and Joshua at the battle of Jericho. They could tell you about Mary, Jesus, God, and the Devil. If you stood around long enough, you’d hear a song about the blind man seeing, God troubling the water, Ezekiel seeing a wheel, Jesus being crucified and raised from the dead. If slaves couldn’t read the Bible, they would memorize Biblical stories they heard and translate them into songs.1

The songs were also used to communicate with one another without the knowledge of their masters. This was particularly the case when a slave was planning to escape bondage and to seek freedom via the Underground Railroad.

Spirituals were created extemporaneously and were passed orally from person to person. These folksongs were improvised as suited the singers. There is record of approximately 6,000 spirituals or sorrow songs; however, the oral tradition of the slaves’ ancestors—and the prohibition against slaves learning to read or write—meant that the actual number of songs is unknown. Some of the best known spirituals include: “Sometimes I Feel Like a Motherless Child,” “Nobody Knows The Trouble I’ve Seen”, “Steal Away,” “Swing Low, Sweet Chariot,” “Go Down, Moses,” “He’s Got the Whole World in His Hand,” “Every Time I Feel the Spirit,” “Let Us Break Bread Together on Our Knees,” and “Wade in the Water.”

With the signing of the Emancipation Proclamation in 1863, the conclusion of the American Civil War, and the ratification of the 13th Amendment to the Constitution officially abolishing slavery in 1865, most former slaves distanced themselves from the music of their captivity. The spiritual seemed destined to be relegated to mention in slave narratives and to a handful of historical accounts by whites who had attempted to notate the songs they heard. Two of the most significant of these accounts are found in Thomas Wentworth Higginson’s Army Life in a Black Regiment, which recounted the slave songs he heard the black Union soldiers sing, and the 1867 publication, Slave Songs of the United States. In the preface of Slave Songs, compiler William Francis Allen described the difficulty they had recording the spirituals they heard:

The best that we can do, however, with paper and types, or even with voices, will convey but a faint shadow of the original. The voices of the colored people have a peculiar quality that nothing can imitate; and the intonations and delicate variations of even one singer cannot be reproduced on paper. And I despair of conveying any notion of the effect of a number singing together, especially in a complicated shout, like “I can’t stay behind, my Lord” (No. 8), or “Turn, sinner, turn O!” (No. 48). There is no singing in parts, as we understand it, and yet no two appear to be singing the same thing—the leading singer starts the words of each verse, often improvising, and the others, who “base” him, as it is called, strike in with the refrain, or even join in the solo, when the words are familiar.2

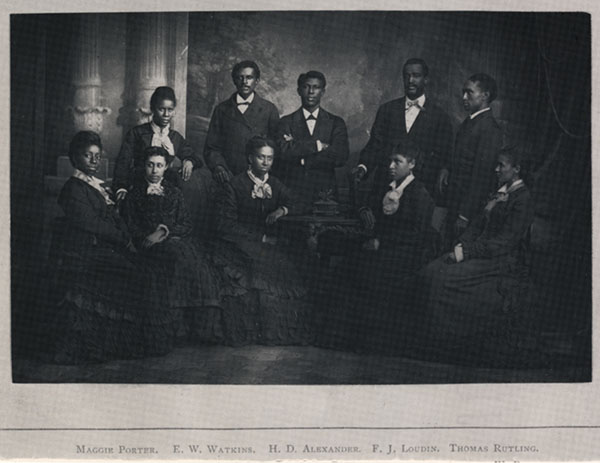

The performance of spirituals was given a rebirth when a group of students from newly founded Fisk University of Nashville, Tennessee, began to tour in an effort to raise money for the financially strapped school. The Fisk Jubilee Singers not only carried spirituals to parts of the United States that had previously never heard Negro folksongs, the musically trained chorus performed before royalty during their tours of Europe in the 1870’s. The success of the Fisk Jubilee Singers encouraged other Black colleges to form touring groups. Professional “jubilee singers” also toured successfully around the world. Collections of “plantation songs” were published to meet the public demand.

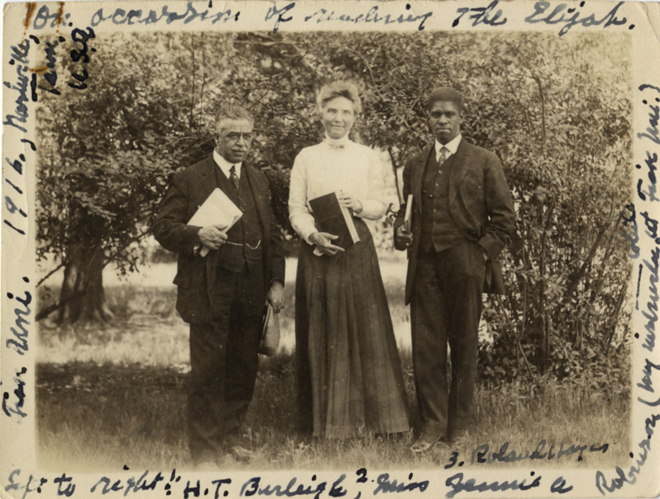

While studying at the National Conservatory of Music, singer and composer Harry T. Burleigh came under the influence of the Czech composer Antonín Dvořák. Dvořák visited the United States in 1892 to serve as the new director of the conservatory and to encourage Americans to develop their own national music. Dvořák learned of the spiritual through his contacts with Burleigh and later commented that:

. . . inspiration for truly national music might be derived from the Negro melodies or Indian chants. I was led to take this view partly by the fact that the so-called plantation songs are indeed the most striking and appealing melodies that have yet been found on this side of the water, but largely by the observation that this seems to be recognized, though often unconsciously, by most Americans. . . . The most potent as well as most beautiful among them, according to my estimation, are certain of the so-called plantation melodies and slave songs, all of which are distinguished by unusual and subtle harmonies, the like of which I have found in no other songs but those of old Scotland and Ireland.3

In 1916, Burleigh wrote the song, “Deep River,” for voice and piano. By that point in his career, he had written a few vocal and instrumental works based on the plantation melodies he had learned as a child. However, his setting of “Deep River” is considered to be one of the first works of its kind to be written in art song form specifically for performance by a trained singer.

“Deep River” and other spiritual settings became very popular with concert performers and recording artists, both black and white. It was soon common for recitals to end with a group of spirituals. Musicians such as Roland Hayes and Marian Anderson made these songs a part of their repertoires. Paul Robeson is credited as being the first to give a solo vocal recital of all Negro spirituals and worksongs in 1925 at the Greenwich Village Theatre, New York, New York.

Over the years, composers have published numerous settings of Negro spirituals specifically for performance on the concert stage, and singers, such as Leontyne Price, Jessye Norman, Kathleen Battle, and Simon Estes, have also successfully recorded them for commercial release.

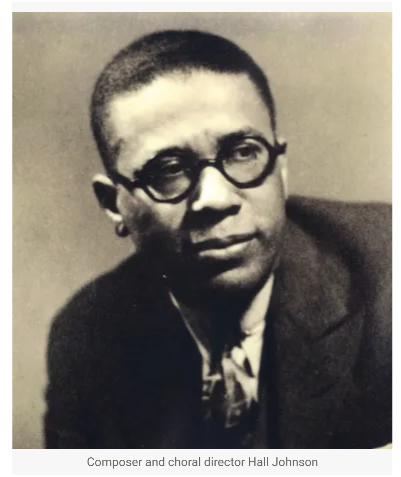

Composers also set spirituals for chorus and organized choral groups on college campuses as well as professional touring choirs. Hall Johnson started the Hall Johnson Negro Choir in September 1925 because he wanted “to show how the American Negro slaves–in 250 years of constant practice, self-developed under pressure but equipped with their inborn sense of rhythm and drama (plus their new religion)–created, propagated and illuminated an art-form which was, and still is, unique in the world of music.”4 His success in the 1930’s through 1950’s was joined over the years by that of Canadian-born Robert Nathaniel Dett, William Levi Dawson, Undine Smith Moore, Eva Jessye, Wendell Whalum, Jester Hairston, Roland Carter, Andre Thomas, Moses Hogan, and many other choral composers who used the spiritual for musical source material.

Additionally, the spiritual has given birth to a number of other American music genres, including Blues, Jazz and gospel. Spirituals played a major role of buoying the spirits of protesters during the Civil Rights Era of the 1950’s and 1960’s. The songs served as a rallying call to those who were demonstrating against laws and policies that kept African Americans from having equal rights.

These art songs challenge both the vocalist and the accompanist to display their technical skills and musicality. More importantly, the songs demand that the musicians tap into the deep well-spring of emotions that inspired those slaves of ages past. As noted by Hall Johnson:

True enough, this music was transmitted to us through humble channels, but its source is that of all great art everywhere—the unquenchable, divinely human longing for a perfect realization of life. It traverses every shade of emotion without spilling over in any direction. Its most tragic utterances are without pessimism, and its lightest, brightest moments have nothing to do with frivolity. In its darkest expressions there is always a hope, and in its gayest measures a constant reminder. Born out of the heart-cries of a captive people who still did not forget how to laugh, this music covers an amazing range of mood. Nevertheless, it is always serious music and should be performed seriously, in the spirit of its original conception.5

True enough, this music was transmitted to us through humble channels, but its source is that of all great art everywhere—the unquenchable, divinely human longing for a perfect realization of life. It traverses every shade of emotion without spilling over in any direction. Its most tragic utterances are without pessimism, and its lightest, brightest moments have nothing to do with frivolity. In its darkest expressions there is always a hope, and in its gayest measures a constant reminder. Born out of the heart-cries of a captive people who still did not forget how to laugh, this music covers an amazing range of mood. Nevertheless, it is always serious music and should be performed seriously, in the spirit of its original conception.5

Whether in a concert performance, joined in congregational singing, or just singing to oneself, spirituals must be sung with an understanding of what forced such powerful songs to rise up from the souls of the men and women who created them. The unknown creators of those American folksongs may no longer be among us, but their longing for freedom and their abiding faith remain to fill our hearts each time we sing these emotionally charged songs.

Soprano Ruby Elzy expressed simply the art of singing spirituals, “the singer who strives to sing the spirituals without the divine spirit will be like the man who plants pebbles and expects them to grow into lilies.”6

The Music

Spirituals fall into three basic categories:

- Call and response – A “leader” begins a line, which is then followed by a choral response; often sung to a fast, rhythmic tempo (“Ain’t That Good News,” “Swing Low, Sweet Chariot,” “Go Down, Moses”)

- Slow and melodic – Songs with sustained, expressive phrasing, generally slower tempo (“Deep River,” “Balm in Gilead,” “Calvary”)

- Fast and rhythmic – Songs that often tell a story in a faster, syncopated rhythm (“Witness,” “Ev’ry Time I Feel the Spirit,” “Elijah Rock,” “Joshua Fit the Battle of Jericho”)

The lyrics dealt with characters from the Old Testament (Daniel, Moses, David) who had to overcome great tribulations and with whom the slaves could easily identify. From the New Testament, the slaves most closely identified with Jesus Christ, who they knew would help them “Hold On” until they gained their freedom. Although slaves often sang about Heaven, the River Jordan—and the hidden reference to Underground Railroad destination, the Ohio River—was regularly a subject of their songs.

Since the rhythm—once established—was key to their songs, the singers would add or delete syllables in words to make them fit the song. Pioneers of spiritual art songs often chose to use dialect, the manner slaves pronounced words, in their settings. Some examples are:

| Heaven – Heav’n, Heb’n, Heb’m | River Jordan – Riber Jerd’n | mourner – mo’ner |

| Children – chillun, chil’n, childun | my – ma, m’ | there – dere |

| for – fer | Morning – mornin’ | more – mo’ |

| the – de | religion – ‘ligion | going to – gwine, gon-ter |

| Jubilee – Juberlee | and – ‘n’, an’ | get – git |

Early vocal settings reflected the goals of pioneering composers to retain as much of the “feel” of the original spiritual as was possible. Choral settings were ideally performed a cappella, and solo vocal pieces allowed the use piano accompaniment for support of the singer. They mainly composed in a steady 2/4 or 4/4 meter.

Over the years, however, compositions have become more tonally and rhythmically complex in both the vocal line and accompaniment. There is less use of dialect. This much more structured approach presents more technical challenges to the performers, but it further erodes their opportunities for expressive interpretation. However, this places greater responsibility upon the performers to be sensitive to the original intent of the music and to communicate that intent to the listener.

_______________

1Velma Maia Thomas. No Man Can Hinder Me: The Journey from Slavery to Emancipation through Song (New York: Crown Publishers, 2001), 14.

2William Francis Allen, Charles Pickard Ware, Lucy McKim Garrison, comp., Slave Songs of the United States (New York, A. Simpson, 1867; reprint, Bedford, MA: Applewood Books, 1995), iv-v.

3Antonín Dvořák, “Music in America,” Harper’s 90 (1895): 432.

4Hall Johnson, “Notes on the Negro Spiritual,” (1965). In Readings in Black American Music, comp. and ed. Eileen Southern, 2nd ed. (New York: W. W. Norton, 1983), 277.

5Johnson. Thirty Spirituals: Arranged for Voice and Piano. (New York: G. Schirmer; dist., Milwaukee, WI: Hal Leonard, 1949), [5].

6Ruby Elzy. “The Spirit of the Spirituals: Religion and Music, a Solution of the Race Problem,” Etude 61, no.8 (August, 1943): 495-496.

SOURCE: http://spirituals-database.com/the-negro-spiritual/#sthash.RsQlMFOI.dpbs

Leave A Comment